The photograph shows a tree stripped of its leaves in winter, its shadow cast against a wall. It’s a simple image at first glance.

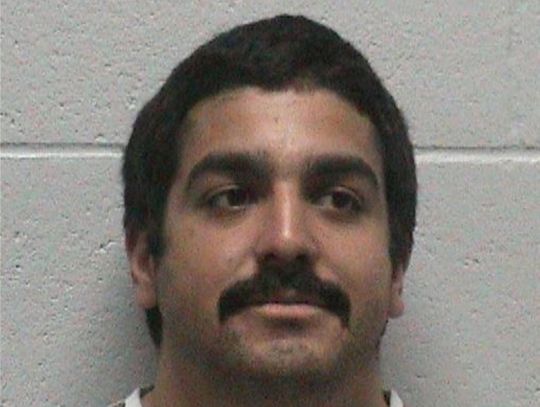

The picture was taken by 72-year-old U.S. Air Force veteran Michael Kukulski, who recently spent more than 60 nights at the Veterans Guest House in Reno while undergoing cancer treatment.

Kukulski enlisted in the Air Force in 1971, first serving as a security policeman in Taiwan before cross-training to become an air operations specialist at Randolph Air Force Base in Texas. There, he worked the dispatch counter for T-38 training pilots, handing out weather data and classified materials and tracking their flights.

Though he liked the job, the only civilian equivalent was an air traffic controller, and when Kukulski left the Air Force, the closest available jobs to his home in Grand Rapids, Michigan, were at Chicago O’Hare International Airport.

“And I did not want to move to Chicago,” Kukulski says. “I got stuck at O’Hare too many times.”

So he moved on, building a civilian career in a variety of jobs, raising a family and eventually winding up in Fernley in November 2018.

Also an avid crafter and gardener, photography became one of his constants. He’s been taking pictures since his parents gave him a Kodak Instamatic camera in second grade and has won several awards in the National Veterans Creative Arts Festival.

On a walk past Silverland Middle School, a tree caught his eye. Its bare branches and straight trunk cast a shadow against a nearby brick wall.

The photo didn’t win any awards, but the judges only saw the image, not the meaning.

The tree, Kukulski says, is himself. The shadow is his identical twin, Patrick, who died at two days old.

He thinks about Patrick almost every day. Sometimes he talks to him. On his walks through the neighborhood, steadying himself with the walker he now uses, he’ll feel a presence beside him, as if his brother is keeping pace.

He didn’t learn he had a twin until he was 8. His parents sat him down in their bedroom and told him he had been born with another baby, a brother, on May 8, 1953. They were more than two months early and so small they had to share an incubator, a rarity in those days. Michael weighed 2 pounds, 12 ounces. Patrick weighed 3½ pounds.

The nurses moved the boys in and out of the incubator as each one struggled to breathe. On Sunday morning, Patrick was placed inside after another round of wheezing. He died soon after.

Michael went back outside to play with the neighborhood kids but remembers being more curious than anything. He had never heard of twins. But the knowledge stayed with him.

At family cemetery visits, he noticed there was no marker for Patrick. When he was turning 16 and his parents asked what he wanted for his birthday, he asked for a gravestone for his brother.

On his birthday, after dinner and cake, the family drove to the Catholic cemetery in their station wagon. They walked to the family plot, and there it was, a small stone etched with the name Patrick Joseph. For the first time, Michael felt connected.

“I felt whole,” he says. “Every time I fly home, I always go see Patrick. And every time I drive on I-80 and see the Patrick exit, I always say, ‘Hey, Patrick.’”

The awareness of Patrick’s absence, and the fragile luck of his own survival, resurfaced when Kukulski began feeling unusually weak in early 2024. He was spending the winter in Indio, California, and chalked up the fatigue to age.

But the sluggishness deepened. He had no appetite and was losing weight.

“I didn’t think a whole lot of it because I figured, well, you’re in your 70s, this is probably what happens,” Kukulski said.

When he returned home in May, his doctor suggested waiting a few months to see if the symptoms improved. By September, he was weaker, thinner and still without an appetite. That’s when the testing began, and on Jan. 2, 2025, the urologist called him with the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

“I didn’t know anything about cancer,” Kukulski said. “I didn’t even know what the prostate did. I just knew I felt lousy.”

Kukulski decided he’d already had too many surgeries in his life and didn’t want another, so he chose radiation. He underwent a procedure to implant six tiny radioactive “seeds” on the left side of his prostate to help guide the radiation.

Because the VA doesn’t provide radiation therapy, Kukulski had to stay in Reno for nine and a half weeks, returning home to Fernley on weekends. Each weekday morning, he reported to Oncology Nevada for treatment.

His final treatment came in mid-October. Ninety days later, he returned for follow-up testing. His PSA, the blood marker used to monitor prostate cancer, had fallen from 8.0 to 0.5.

As excited as he was about that result, doctors warned Kukulski that his age, two previous heart attacks, high blood pressure and diabetes complicate the picture. There’s no guarantee the cancer won’t return to either the prostate or another part of the body.

“Celebrate your PSA,” they told him, “but also walk cautiously because anything could happen.”

Kukulski has taken that message to heart. With World Cancer Day approaching on Feb. 4, he describes the mindset as a way of moving through the world after months of fear, frustration and uncertainty.

“The first three or four months you do crying, you’re upset, you’re nerved up, you complain,” Kukulski said. “Finally I came to the conclusion that everybody’s gonna go. You don’t know how you’re gonna go, and you had a twin brother, Patrick, that died at two days old. He never had a chance to live all the life that you have. So be grateful.”

Looking at the life he’s lived—the travel, the moves, the jobs—Kukulski said he realized he’s lived both his life and the one Patrick never had.

“So for some reason, if this takes me out, so be it,” he said. “I gotta go somehow. But until then, I do everything I can to try to have fun every day.”

Comment

Comments