Local health districts grapple with coronavirus after years of ‘whack-a-mole’ public health funding

By Megan Messerly

https://thenevadaindependent.com

On the first day of the third week of the 2019 legislative session, the lawmakers on the Assembly Health and Human Services Committee were finally ready to get to work.

After sitting through two weeks of presentations, the first bill to come before the committee was a short, six-page proposal, one of the simpler pieces of policy the committee would hear during the session. Its title, too, was succinct: “Revises provisions relating to certain expenditures of money for public health.”

The primary purpose of the bill, which was sponsored by the committee, was to establish a public health improvement account in the state’s general fund and appropriate $15 million to it. Those funds were to be divided by population and distributed to local health districts or, where applicable, the state, which serves as the public health authority for 14 of Nevada’s 17 counties. Each entity was to evaluate the public health needs of the residents it serves, prioritize those needs and then spend the money accordingly. The goal: Give health districts more dollars and greater capacity to respond to emerging public health threats.

It wasn’t an unusual ask. Many entities come before the Legislature each session asking for a slice of the state’s financial pie. But it was the last anyone would hear of the bill.

The legislation, AB97, stood to have a significant impact on public health agencies in Nevada, where discretionary funds are few and far between, while program-specific, limited-duration grant dollars with lots of strings attached are plentiful. The legislation could have allowed the public health community in Nevada to be proactive to respond to health needs as they develop and not — as they often lament they’re forced to be — reactive.

“This investment in public health is very important to improve the health of our population,” Washoe County District Health Officer Kevin Dick told the committee during the February 2019 hearing. “It allows us to support data-driven community health assessment approaches to address priority health needs in our communities and, ultimately, the flexibility in this funding allows health authorities to address the root causes and social determinants of health.”

According to a recent report from the Commonwealth Fund, Nevada ranks 50th in the nation in public health spending per capita, with $8 spent on public health per Nevadan. (Missouri is last, spending $7 per person, New Mexico is first, at $137 per person, and the national average is $37.) With about 3 million residents in Nevada, the $15 million appropriation suggested by AB97 would have meant an extra $5 in spending per person on public health in the state.

Dick, during the hearing, called the sum the “gorilla in the room,” noting that the Department of Health and Human Services had requested the funding as part of its budget but did not receive it. He said he was hopeful during the session lawmakers might find an extra $15 million to allocate.

The dollars would have helped public health agencies build capacity to provide their usual suite of services, like family planning care and restaurant inspections, as well as address social determinants of health where the state is weak, such as violent crime and low immunization rates. But Dick also asked that at least some of the funding be reserved in the account in the event of a public health emergency — a sort of rainy day fund for public health.

“Now when the interim committee discussed this … there was concern that if the funds all remained in the account, we might end up with a situation where the state faced other needs and yet this money was unavailable because it was in the account for public health improvement,” Dick said. “But I think we need to consider trying to at least allocate part of any remaining unspent funds to remain in the account, up to a certain limit so that we do have funds for public health emergencies.”

The most pressing threat at the time was measles, with 1,282 cases reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2019. Dick noted that a measles outbreak in Minnesota — of just 22 cases — was estimated by the CDC to have cost that state between $920,000 and $1.6 million.

During the session, lawmakers did find money for two public health initiatives: $6 million for family planning services, and $5 million to control and prevent the use of tobacco. But AB97 never received a second hearing. Multiple sources who followed the legislation attributed the bill’s death to the mid-session resignation of Assemblyman Mike Sprinkle. The Sparks Democrat had been shepherding the bill as chair of the Assembly Health and Human Services committee before he stepped down amid allegations of sexual harassment.

Now, a year later, the state’s underfunded health agencies are grappling with a public health emergency far bigger than measles. The novel coronavirus has infected more than 700 people and claimed the lives of 14 across the state, most of them in Clark County.

Even the most well-funded health departments across the country are struggling to provide necessary services related to the COVID-19 outbreak — things like case monitoring and contact tracing. This means Nevada’s local health agencies would still face an uphill battle even had they received AB97’s $15 million appropriation. But experts say the coronavirus pandemic is underscoring the historic lack of investment in public health agencies, which, in the time of coronavirus, have pivoted almost all of their limited resources to deal with the pandemic.

“It’s a nationwide problem. A lot of health departments across the country are struggling with cuts,” said John Packham, associate dean for the Office of Statewide Initiatives at UNR’s School of Medicine and chair of the Nevada Public Health Association’s advocacy and policy committee. “The irony is that those cuts were taking place during economic good times, and that’s kind of the disturbing part.

“If you pay for public housing or public education, you can at least see a tangible result, a new school or a teacher hired or somebody getting a place to live. But with public health, it’s tracking COVID-19,” he continued. “How do you see or measure that until it’s blown up on you? That’s kind of what we’re paying for.”

The situation in Southern Nevada

The first confirmed case of the novel coronavirus in Nevada was reported in Southern Nevada on March 5. The patient was a man in his 50s who had recently traveled to Washington state; at the time, the state was the center of the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. The next day, Nevada saw another case; by the next week, there were 11 statewide.

Now, a little more than three weeks later, the Southern Nevada Health District is struggling to keep up. More than 500 people are confirmed to be infected with the virus in Clark County, and likely many more cases are going undiagnosed as testing remains limited across the U.S.

Initially, only two labs in the state tested for COVID-19. The Southern Nevada Public Health Laboratory was responsible for tests in Clark County, while the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory in Reno ran tests for everywhere else. But only a week and a half after the first confirmed case, and the Southern Nevada lab was already running out of supplies and sending samples to Reno for testing. The lab is now only providing testing for health district contact investigations and other priority investigations, while the bulk of testing for the general public falls on commercial labs.

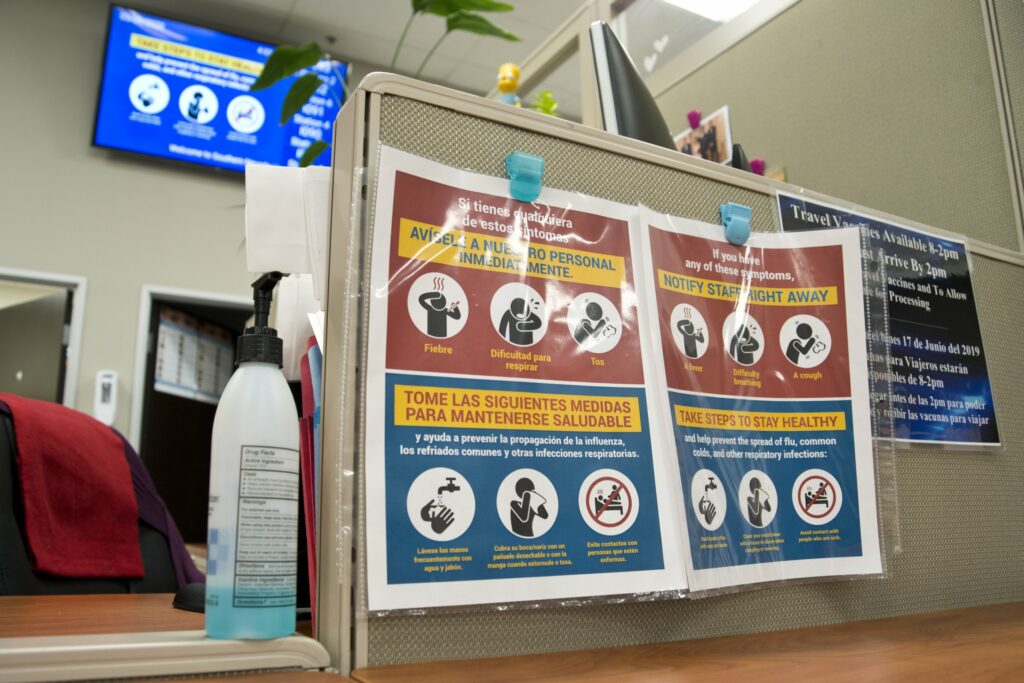

Additionally, the health district has pulled in much of its staff — as of December, about 550 full-time equivalent employees — to assist with its response to COVID-19. The health district is continuing to offer clinical services to the community, but additional services have been either suspended or moved online.

“The main function of our health district is to respond to this outbreak,” Dr. Fermin Leguen, the district’s chief health officer, said in an interview this week. “We have deployed employees who are working in areas not related to surveillance. For example, we assigned them to support surveillance or to support clinic areas or other things that are related.”

The Southern Nevada Health District has the biggest annual budget of Nevada’s local health agencies, about $72 million. The largest chunk is funded by property taxes, a revenue stream that local governments across the state have long complained has not kept up with growth and recovery in the wake of the Great Recession, and which the Legislature took no steps to address during the last session.

North Las Vegas City Councilman Scott Black, who chairs the Southern Nevada Health District’s board, said property taxes now look like an even more unstable funding source with an economy in turmoil.

“Property tax, that’s about a third of our income, our revenue,” Black said. “We have no idea what’s coming down, three, six, nine, 12 months down the road as we look at our budget. It’s a vast and foggy unknown, and it’s scary.”

Another fifth of the health district’s budget is funded by intergovernmental grants, either from the state or federal governments. But that funding is also unreliable: the kinds of available grants along with how much they’re worth change yearly, and many come with a significant number of conditions, influencing how health districts allocate resources.

Leguen noted the health district lost a $700,000 federal grant last year that supported a program for new mothers, their families and early childcare. When those grants dry up or disappear, the health district has to figure out how to re-shuffle its staff or, ultimately, let them go.

“That’s a challenge for any public health organization across the country because when you receive a federal grant typically it is limited to a certain number of years, and after that period expires there might be another grant following the initial cycle,” Leguen said. “In most grants, one of the areas that is discussed is sustainability. But when you talk about losing $500,000 or $1 million, it becomes difficult for a health department to somehow reincorporate that funding.”

The final two significant sources of health district revenue are charges for services, and licenses and permits. But Black noted the health district actually has to provide those services and carry out its oversight role in order to earn that funding — a more difficult prospect in the middle of a pandemic.

“Out of those four pipelines of revenue to serve our communities, we have not one stable source of revenue that we can count on year over year that we can use as the base of our operating expenditures,” Black said.

The health district has also, generally, struggled to recover in the wake of the recession. Brian Labus, an assistant professor of public health at UNLV and former senior epidemiologist for the Southern Nevada Health District, said SNHD went through a period of layoffs during the recession, but the bigger problem was the health district had a lot of positions that it couldn’t fill.

“We couldn’t put in place these programs we desperately needed,” said Labus, who worked at the health district from 2001 to 2015. “We faced the same challenges that everyone did nationwide in an economic downturn.”

The health district has grown its staff between 15 and 20 percent in the last three years, Leguen said, but it still struggles to recruit enough people to meet the demand for services. It’s a problem familiar to those who work in health care in Nevada — there simply aren’t enough health care providers in the state. It’s exacerbated for SNHD because it can’t afford to pay salaries as competitive as those offered by private health care companies, and because of Clark County’s rapidly growing population.

“Here in Southern Nevada, we are competing for health professionals with our community partners. We’re talking about competing for the services of nurses, physicians, support staff, also information system engineers, all of those kinds of professions that also complement the services that we do,” Leguen said. “Here in Las Vegas, for us, the challenge is bigger because of the lack of enough professionals for most of those areas.”

But it’s not just the Southern Nevada Health District that is struggling under the weight of the current crisis. Many health districts across the country experienced cuts over the last decade that have made it more difficult for them to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic simply because of limited resources and staffing.

“I wish I could say any of these problems are unique to Nevada,” Labus said. “But if you talk to anybody at any health department in the country, even the better funded ones are underfunded.”

The public health funding landscape in Nevada

Not only does Nevada have the second-lowest spending on public health per capita, most of it comes from the federal government. A recent study by the Guinn Center found 98.2 percent of the $11.4 million in funding for Nevada’s public health preparedness program — responsible for planning for public health emergencies, primary care planning, provider recruitment and retention and EMS response — is federal dollars.

“What surprised me was the degree of reliance on federal funding. When I went into this, I was looking at the public health emergency program and then just the public health preparedness, and I was expecting to see a state general fund contribution,” said Meredith Levine, the Guinn Center’s director of economic policy. “As I started to poke through the revenue sources and saw it was 98.2 percent federal, for me, that was the surprise finding in all of this.”

It’s not just on the public health preparedness side of the equation either. Packham, the associate dean at UNR’s School of Medicine, noted many public health initiatives, including chronic disease funding, the HIV/AIDS program and immunization, are primarily funded by the federal government, whether through CDC funding or the federal Health Resources and Services Administration.

The state Division of Public and Behavioral Health has other funding sources too, such as state general fund dollars and fees generated through inspections. But the bottom line, Packham said, is that Nevada is “heavily reliant” on the federal government to fund core public health activities, not just supplemental ones. And those funding sources don’t often give the state or local health agencies much flexibility when it comes to identifying their own immediate public health needs and funding them.

“When you have a new threat particularly like these infectious disease outbreaks, there are dollars you can move around, but most of the dollars, they’re earmarked for certain things. If you get dollars for TB control, that’s what you have to spend it on,” Packham said. “You don’t necessarily have discretionary dollars you can devote to a disease outbreak that’s new. You don’t necessarily have dollars to do investigations into the vaping issues that came out of nowhere in the last three to four years.”

Packham said AB97 would have given health districts greater financial flexibility to respond to public health needs as they are identified.

“When COVID-19 has gone away, something else will pop up,” he said. “It’s whack-a-mole.”

The primary criticism from public health experts is that the reactive funding approach often taken with public health is in direct contrast to the way that public health is supposed to work.

“After 9/11, a ton of money went into public health preparedness but over time that money started to shrink. When West Nile happened, we dumped a ton of money into vector borne disease. Then Zika showed up,” Labus said.

Heidi Parker, the executive director of the nonprofit immunization organization Immunize Nevada, said federal grants help fill gaps in the short term. When they lapse, though, whatever particular area of public health it was addressing goes back to being underfunded.

“That’s what we’re going to see happen with COVID too,” Parker said. “We’re going to get this influx of funding and it’s going to help in the short term, but what’s going to happen in the long term?”

The state has, in recent years, invested additional dollars in public health efforts, such as the appropriations toward tobacco prevention and education and family planning services last session. Sen. Julia Ratti, who chairs the Senate Committee on Health and Human Services, referred to them as “public health wins.”

“They’re not necessarily general fund dollars that build capacity or emergency capacity,” Ratti said. “But they send a very clear message that we have not been ignoring public health. We’ve had a couple of really big victories.”

A recent report from Trust for America’s Health shows public health spending in Nevada increased by 40 percent between 2018 and 2019. Still, public health experts say there’s plenty of room to grow.

“That sounds really great until you realize you could have a 40 percent increase if you were starting out from a small place to begin with,” Packham said. “I don’t view that as the health division’s problem. That’s a political problem that has bipartisan roots. We’re just stingy when it comes to funding public health.”

Dick told lawmakers last year in his presentation on AB97 that where other states fund 21 percent of local health department budgets, the Southern Nevada Health District and Washoe County Health Districts only receive 1 percent of their funding from the state, while Carson City Health and Human Services gets about 4 percent.

Another complicating factor is that the state is in the unique position of applying for federal funds and sub-granting those to local health agencies and other organizations as the state of Nevada — while also serving as the direct provider of public health services to 14 rural Nevada counties. That has, historically, caused some tension over how those resources are doled out across the state.

“When there’s not enough money to go around, there’s going to be tension,” Labus said. “The state’s facing the same challenges that all of the local health departments are. They are the ones controlling the funding coming from the CDC. Of course that’s going to cause tension.”

(The Department of Health and Human Services did not make anyone available to answer questions on the state’s public health funding landscape for this article but did provide The Nevada Independent with a number of documents and other resources detailing the public health funding situation in Nevada.)

Even if the state were to invest additional dollars in public health moving forward — a decision that would be up to the Legislature and governor — there is no guarantee those dollars would remain a stable funding source moving forward. Packham noted that 10 percent of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement funds Nevada received used to flow into what was called a “Trust Fund for Public Health.”

“We started funding public health programs with just the interest. It was phenomenal. It was like an endowed chair at a university paid for by just the interest that was accumulating and that 10 percent we kept socking away,” Packham said. “But when the recession in 2008 and 2009 hit, that was all swept away into the general fund.”

Packham said even states with significantly better public health outcomes than Nevada still rely on the federal government for support. But they also have stable state funding revenues — like a state income tax or a better property tax structure — to allow them to support state investment in public health.

“The double whammy in Nevada is our budget. We not only don’t have a state income tax, we’re so reliant on gaming and tourism that like the Great Recession, you know what happens to our revenues. You get a little more Medicaid funding and some other stuff, but it doesn’t offset the ability to fund public health,” Packham said. “If there’s a story it’s that we don’t fund public health in economic boom times.”

The broader, philosophical question is this: Where should the burden of funding public health fall? The federal government? The state? Local governments?

For Labus, the answer is simple.

“Under the Constitution, public health becomes a state and local issue, and they’re responsible for putting the programs in place that they need to protect their citizens,” Labus said. “The federal government is there providing extra funding for all sorts of programs, including the problem we’re dealing with right now. But it’s not their responsibility to take care of every single health department in the country. It’s something that the local governments and state governments need to fund.”

But public health experts acknowledge it’s difficult to think about investing significant sums of money in public health, when the results could take decades to manifest. There’s an immediate payoff in putting additional dollars into a classroom today and seeing effects tomorrow.

“People are used to seeing immediate things, like coronavirus, but if we put in place an amazing cancer prevention program right now, we wouldn’t see the benefits of that for decades,” Labus said. “Public health is a very tough sell because if we do our jobs right, people don’t know that we did them because they never got sick. So how do you convince people to pay for something they don’t see the outcome of?”

Public health in rural Nevada

When Lyon County had its first confirmed case of coronavirus on Wednesday, the notification process worked exactly as it was supposed to, Dr. Robin Titus, the county’s health officer, said.

The man recently sailed on a cruise ship and visited San Francisco. He was then tested in Washoe County. When his results came back positive, Washoe County reached out to the Quad County Emergency Operations Center, which serves as the response hub for Douglas, Storey and Lyon Counties, as well as Carson City. The center immediately contacted Titus.

In non-pandemic times, Carson City Health and Human Services operates as its own local health agency, providing some services for Douglas County; the other three counties are served by the state. For purposes of emergency response, the four jurisdictions join forces as the Quad Counties.

Rural Nevada does not, in general, have the kind of public health infrastructure that urban Clark and Washoe counties do. But, all things considered, Titus said, the process in Lyon County has been working well so far.

“We don’t have enough to stand up our own huge areas, so we combine resources,” said Titus, who is also an assemblywoman and heads the Assembly Republican Caucus. “I feel our public health system has done a great job with this.”

It’s the kind of public health operation Lyon County would like to see all the time. Shayla Holmes, director of Lyon County Human Services, said the Quad Counties and nearby Churchill County have been trying to work together to identify funding to pay for a study on cross-jurisdictional health districts in Nevada. Right now, rural counties pay the state for the services the Division of Public and Behavioral Health provides them, like community health nurses who offer family planning and vaccination services to local residents.

“There is a contract in place. I’ve tried negotiating that. I don’t win, but I try,” Holmes said. “We pay an assessment for each of the community health nurses out here in Lyon County. I don’t get any say over what they do. I have to provide the office space for them. They break it down for me on how those monies are used, but I don’t have any oversight.”

But Holmes said even if the counties were able to pool the money they send to the state, it still wouldn’t be enough to fund a regional health district. If the health district existed, they could apply for grant funding to help sustain it. But, without additional funding, they can’t form the district to get the funding.

It is, in essence, a chicken and the egg problem.

“The individuals we work with at the state do want to see enhancements to the system. We don’t meet a lot of resistance with the state when it comes to trying to engage them with, ‘How do we become more localized?’” Holmes said. “The problem is the way that (state law) is set up with the funding streams, any funding that I get with regards to being able to increase public health outcomes I really only have one option, and that’s to go with the state.”

For the remaining rural counties, the coronavirus pandemic may prove an even bigger test, since they don’t have a Quad County-style operation to lean on. Joan Hall, president of Nevada Rural Hospital Partners, said some rural hospitals didn’t know until recently that the Division of Public and Behavioral Health serves as their public health authority.

“Some people are going, ‘Oh my gosh, who should get what information?’ It’s an issue. Thank goodness we haven’t had many positive cases in the rurals,” Hall said. “It just shows from a rural perspective our lack of awareness of the public health process, and it’s more than just the hospitals. We wish we could spend more time on public health, but that’s not really our directive.”

Hall said the relationship between the state, local hospitals, the county medical officer and the county’s board of health were not well defined.

“Hospitals get together with emergency management to talk about flooding and wildfires and blizzards and how we’re going to all work together on singular outbreaks of norovirus. It’s been a whole test of the whole system,” Hall said. “I don’t think there’s blame to be placed on anybody, but I don’t think this was ever envisioned.”

The other difficulty, Hall said, is that rural hospitals had planned to lean on each other in the event of an emergency. In the past, hospitals would send each other personal protective equipment, medicine, rapid flu tests, blood and even nurses, she said, but now resources are scarce all around.

“We never thought the person we would ask for help wouldn’t be able to help us either,” Hall said.

Combatting coronavirus

In the short term, public health agencies have received additional resources from the federal government to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Southern Nevada Health District received $2.3 million from the CDC this week, while the Washoe County Health District received a little more than $900,000, out of $6.5 million the state received from the CDC.

Leguen, SNHD’s chief health officer, said the new funds could be used for a number of different purposes, including supporting local response, lab resources, surveillance, or personal protective equipment. But that money isn’t going to be able to grow the kind of long-term capacity, such as additional staff and more health districts in rural corners of the state, that could help the state better combat coronavirus.

As recently as December, public health advocates pushed lawmakers during a meeting of the Legislature’s Interim Health Care Committee to establish a public health improvement fund and invest in public health infrastructure in Nevada. It’s the first priority listed by the Nevada Public Health Association on its 2020 policy agenda.

Ratti, the Senate’s health care committee chair, framed it as a balancing act for lawmakers between meeting pressing, current needs and planning for the future.

“The trick is, how do you be a good steward of the finances that are available? We don’t want to be setting a bunch of money aside to meet the critical needs of vulnerable Nevadans or the health and human services needs of Nevadans and have it all squirreled away for an emergency,” Ratti said. “But you want to have the capacity to address emergencies when they come.”

Although the state does not have dedicated public health emergency funds stashed away, it does have $401 million in general rainy day funds the Legislature has socked away after years of neglecting the account. Money can only be taken from the account if tax revenues fall below projections or state leaders declare a fiscal emergency.

“Certainly having that rainy day fund gives the overall system the ability to have the flexibility to make smart decisions and not have to make very quick decisions that may have sharper, steeper longer term consequences. I’m proud of that,” Ratti said. “I think the thing that has been challenging over the last several weeks is there were things we thought we could rely on from the federal government that have been difficult to access and that is hurting us at the state and local levels.”

Two decades ago, a storm dumped billions of gallons of water on Las Vegas in just a couple of hours, killing two people and causing millions of dollars in damage. It was known as the 100-year flood.

Black, the chair of the Southern Nevada Health District board, said the coronavirus pandemic is now the 100-year public health emergency flood.

“And we’re not ready for it,” Black said. “AB97 was a good first attempt, but I think we need to revisit that and look at what that means for us moving forward. You look at the sunny skies and say, ‘Why are we spending all of this money?’ And then the rain comes down and the waters come in from the canyons.”

The difficulty is, if public health officials are doing their job, that flood will never come.

“Outbreaks like this certainly help public health come to the front of people’s minds. We start thinking about disease differently and what we need in place to respond but as soon as this emergency is done there will be another one,” Labus said. “This is kind of the constant fight for public health. If you’re doing a good job you’re preventing things, and no one will ever see it.”